Saturday, October 14, 2017

MLB Ejection P-2 - Mike Winters (2; Joe Maddon)

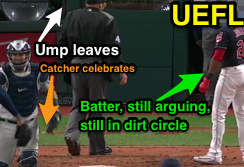

2B Umpire Mike Winters ejected Cubs Manager Joe Maddon for arguing a Replay Review decision that overturned HP Umpire Lance Barksdale's collision violation no-call in the bottom of the 7th inning of the Cubs-Dodgers game. With one out and two on (R1, R2), Dodgers batter Justin Turner hit a 1-0 fastball from Cubs pitcher John Lackey on a ground ball to left fielder Kyle Schwarber, who threw to catcher Willson Contreras as Dodgers baserunner R2 Charlie Culberson slid toward home plate, ruled out by HP Umpire Barksdale. Upon Replay Review as the result of a Manager's Challenge by Dodgers Manager Dave Roberts, Barksdale's ruling was overturned to "safe" pursuant to HP Collision/plate blocking Rule 6.01(i)(2), the call was correct.* At the time of the ejection, the Dodgers were leading, 5-2. The Dodgers ultimately won the contest, 5-2.

This is Mike Winters (33)'s second ejection of 2017.

Mike Winters now has 6 points in the UEFL Standings (3 Prev + 2 MLB + 1 Correct-Crewmate = 6).

Crew Chief Mike Winters now has 8 points in Crew Division (7 Previous + 1 Correct Call = 8).

*OBR 6.01(i)(2) states, "Unless the catcher is in possession of the ball, the catcher cannot block the pathway of the runner as he is attempting to score. If, in the judgment of the umpire, the catcher without possession of the ball blocks the pathway of the runner, the umpire shall call or signal the runner safe. Not withstanding the above, it shall not be considered a violation of this Rule 6.01(i)(2) (Rule 7.13(2)) if the catcher blocks the pathway of the runner in a legitimate attempt to field the throw (e.g., in reaction to the direction, trajectory or the hop of the incoming throw, or in reaction to a throw that originates from a pitcher or drawn-in infielder)."

*OBR 6.01(i)(2) Comment states, in part, "A catcher shall not be deemed to have hindered or impeded the progress of the runner if, in the judgment of the umpire, the runner would have been called out notwithstanding the catcher having blocked the plate."

*This is the 13th Replay Review of a HP Collision play in 2017, and first overturned call.

This is the 186th ejection report of 2017, 2nd of the postseason.

This is the 88th Manager ejection of 2017.

This is Chicago-NL's 6th ejection of 2017, T-1st in the NL Central (CHC, CIN, MIL, PIT 6; STL 4).

This is Joe Maddon's 3rd ejection of 2017, 1st since August 16 (Chris Conroy; QOC = Y [Check Swing]).

This is Mike Winters' 2nd ejection of 2017, 1st since May 20 (Bob Melvin; QOC = Y [Base Award]).

Wrap: Chicago Cubs vs. Los Angeles Dodgers (NLCS Game 1), 10/14/17 | Video as follows:

This is Mike Winters (33)'s second ejection of 2017.

Mike Winters now has 6 points in the UEFL Standings (3 Prev + 2 MLB + 1 Correct-Crewmate = 6).

Crew Chief Mike Winters now has 8 points in Crew Division (7 Previous + 1 Correct Call = 8).

*OBR 6.01(i)(2) states, "Unless the catcher is in possession of the ball, the catcher cannot block the pathway of the runner as he is attempting to score. If, in the judgment of the umpire, the catcher without possession of the ball blocks the pathway of the runner, the umpire shall call or signal the runner safe. Not withstanding the above, it shall not be considered a violation of this Rule 6.01(i)(2) (Rule 7.13(2)) if the catcher blocks the pathway of the runner in a legitimate attempt to field the throw (e.g., in reaction to the direction, trajectory or the hop of the incoming throw, or in reaction to a throw that originates from a pitcher or drawn-in infielder)."

*OBR 6.01(i)(2) Comment states, in part, "A catcher shall not be deemed to have hindered or impeded the progress of the runner if, in the judgment of the umpire, the runner would have been called out notwithstanding the catcher having blocked the plate."

*This is the 13th Replay Review of a HP Collision play in 2017, and first overturned call.

This is the 186th ejection report of 2017, 2nd of the postseason.

This is the 88th Manager ejection of 2017.

This is Chicago-NL's 6th ejection of 2017, T-1st in the NL Central (CHC, CIN, MIL, PIT 6; STL 4).

This is Joe Maddon's 3rd ejection of 2017, 1st since August 16 (Chris Conroy; QOC = Y [Check Swing]).

This is Mike Winters' 2nd ejection of 2017, 1st since May 20 (Bob Melvin; QOC = Y [Base Award]).

Wrap: Chicago Cubs vs. Los Angeles Dodgers (NLCS Game 1), 10/14/17 | Video as follows:

Labels:

Ejections

,

HP Collision

,

Instant Replay

,

Joe Maddon

,

Mike Winters

,

QOCY

,

UEFL

Friday, October 13, 2017

Discussion of 2017 AL & NL League Championship Series

Discussion for the 2017's postseason's AL and NL League Championship Series is open.

Home plate umpire performance is listed following the completion of each contest according to pitch f/x and UEFL Rules 6-2-b-a (horizontal bound, "Kulpa Rule") and 6-2-b-b (vertical strike zone, "Miller Rule"). Callable pitches (which excludes all swinging strikes, fair and foul balls, HBPs, and pitchouts) are organized by type: "ball" or "called strike."

For instance, if a line score reads "49/50 Strikes," that signifies that of 50 total pitches ruled "strike" 49 were officiated correctly, while one pitch called "strike" was located outside of the strike zone.

Plays include significant plays and instant replay reviews, if such plays occur. Call +/- also included/highlighted.

- 10/13 NYY@HOU Gm 1: Chad Fairchild: pfx. 104/104 Balls + 45/49 Strikes = 149/153 = 97.4%. +0.

- 10/14 NYY@HOU Gm 2: Hunter Wendelstedt: pfx. 72/73 Balls + 44/47 Strikes = 116/120 = 96.7%. +0.

- 10/14 CHC@LAD Gm 1: Lance Barksdale: pfx. 105/107 Balls + 46/53 Strikes = 151/160 = 94.4%. +3 LA.

- 10/15 CHC@LAD Gm 2: Todd Tichenor: pfx. 105/111 Balls + 51/52 Strikes = 156/163 = 95.7%. +3 LA.

- 10/16 HOU@NYY Gm 3: Gary Cederstrom: pfx. 105/113 Balls + 53/59 Strikes = 158/172 = 91.9%. +0.

- 10/17 HOU@NYY Gm 4: Chris Guccione: pfx. 107/109 Balls + 38/42 Strikes = 145/151 = 96.0%. +4 NY.

- 10/17 LAD@CHC Gm 3: Mike Winters: pfx. 99/103 Balls + 46/49 Strikes = 145/152 = 95.4%. +3 LA.

- 10/18 HOU@NYY Gm 5: Jerry Meals: pfx. 94/97 Balls + 49/56 Strikes = 143/153 = 93.5%. +0.

- 10/18 LAD@CHC Gm 4: Jim Wolf: pfx. 98/100 Balls + 45/51 Strikes = 143/151 = 94.7%. +6 LA.

- 10/19 LAD@CHC Gm 5: Bill Welke: pfx. 93/96 Balls + 48/51 Strikes = 141/147 = 95.95%. +0.

Series Complete: NLCS LAD Over CHC 4-1, 95.2%, 736/773, Net Skew: +15 LA Dodgers.

- 10/20 NYY@HOU Gm 6: Jim Reynolds: pfx. 98/103 Balls + 42/47 Strikes = 140/150 = 93.3%. +4 NY.

- 10/21 NYY@HOU Gm 7: Mark Carlson: pfx. 83/85 Balls + 37/41 Strikes = 120/126 = 95.2%. +4 NY.

Series Complete: ALCS HOU Over NYY 4-3, 94.7%, 971/1025, Net Skew: +12 NY Yankees.

NOTE: The highest plate score during the 2016 Championship Series was Jim Wolf's 98.6% (ALCS 2).

The highest plate score overall during the 2016 Postseason was Jim Wolf's 98.6% (ALCS Game 2).

Instant Replay Reviews (R-QOC Colors: Green [Confirmed], Yellow [Stands], Red [Overturned]):

- ALCS-1 HP Umpire Chad Fairchild's out call on play at the plate is confirmed.

- ALCS-2 RF Umpire Chad Fairchild's home run call is confirmed to give Astros an early lead.

- ALCS-2 3B Umpire Jerry Meals' safe call is overturned to negate Gardner's triple.

- NLCS-1 2B Umpire Mike Winters' safe call on Bellinger's stolen base stands.

- NLCS-1 HP Umpire Lance Barksdale's collision violation no-call (out) is overturned; Maddon ejected.

- ALCS-3 HP Umpire Gary Cederstrom's HBP-no call stands as Replay cannot deduce ball's status.

- ALCS-3 1B Umpire Chris Guccione's safe call is overturned as infield single turns into a groundout.

- ALCS-4 1B Umpire Jerry Meals' out call is overturned, but Judge is still retired one play later.

- ALCS-4 2B Umpire Jim Reynolds' safe call is confirmed on Headley's late rallying base hit.

- NLCS-3 LF Umpire Eric Cooper's lodge call is confirmed as ball gets stuck in the Wrigley Field ivy.

- NLCS-4 1B Umpire Bill Welke's out call on attempted bunt single is confirmed in 5th inning.

- ALCS-6 HP Umpire Jim Reynolds' HBP-no call is overturned and Castro is awarded first base.

- ALCS-7 1B Umpire Hunter Wendelstedt's out call is confirmed at first base on pulled foot call.

Totals: 6 Confirmed + 2 Stands + 5 Overturned = 8/13 = .615 RAP.

NOTE There were 11 Replay Reviews during the 2016 LCS (4/11 = .364 RAP).

Home plate umpire performance is listed following the completion of each contest according to pitch f/x and UEFL Rules 6-2-b-a (horizontal bound, "Kulpa Rule") and 6-2-b-b (vertical strike zone, "Miller Rule"). Callable pitches (which excludes all swinging strikes, fair and foul balls, HBPs, and pitchouts) are organized by type: "ball" or "called strike."

For instance, if a line score reads "49/50 Strikes," that signifies that of 50 total pitches ruled "strike" 49 were officiated correctly, while one pitch called "strike" was located outside of the strike zone.

Plays include significant plays and instant replay reviews, if such plays occur. Call +/- also included/highlighted.

- 10/13 NYY@HOU Gm 1: Chad Fairchild: pfx. 104/104 Balls + 45/49 Strikes = 149/153 = 97.4%. +0.

- 10/14 NYY@HOU Gm 2: Hunter Wendelstedt: pfx. 72/73 Balls + 44/47 Strikes = 116/120 = 96.7%. +0.

- 10/14 CHC@LAD Gm 1: Lance Barksdale: pfx. 105/107 Balls + 46/53 Strikes = 151/160 = 94.4%. +3 LA.

- 10/15 CHC@LAD Gm 2: Todd Tichenor: pfx. 105/111 Balls + 51/52 Strikes = 156/163 = 95.7%. +3 LA.

- 10/16 HOU@NYY Gm 3: Gary Cederstrom: pfx. 105/113 Balls + 53/59 Strikes = 158/172 = 91.9%. +0.

- 10/17 HOU@NYY Gm 4: Chris Guccione: pfx. 107/109 Balls + 38/42 Strikes = 145/151 = 96.0%. +4 NY.

- 10/17 LAD@CHC Gm 3: Mike Winters: pfx. 99/103 Balls + 46/49 Strikes = 145/152 = 95.4%. +3 LA.

- 10/18 HOU@NYY Gm 5: Jerry Meals: pfx. 94/97 Balls + 49/56 Strikes = 143/153 = 93.5%. +0.

- 10/18 LAD@CHC Gm 4: Jim Wolf: pfx. 98/100 Balls + 45/51 Strikes = 143/151 = 94.7%. +6 LA.

- 10/19 LAD@CHC Gm 5: Bill Welke: pfx. 93/96 Balls + 48/51 Strikes = 141/147 = 95.95%. +0.

Series Complete: NLCS LAD Over CHC 4-1, 95.2%, 736/773, Net Skew: +15 LA Dodgers.

- 10/20 NYY@HOU Gm 6: Jim Reynolds: pfx. 98/103 Balls + 42/47 Strikes = 140/150 = 93.3%. +4 NY.

- 10/21 NYY@HOU Gm 7: Mark Carlson: pfx. 83/85 Balls + 37/41 Strikes = 120/126 = 95.2%. +4 NY.

Series Complete: ALCS HOU Over NYY 4-3, 94.7%, 971/1025, Net Skew: +12 NY Yankees.

NOTE: The highest plate score during the 2016 Championship Series was Jim Wolf's 98.6% (ALCS 2).

The highest plate score overall during the 2016 Postseason was Jim Wolf's 98.6% (ALCS Game 2).

Instant Replay Reviews (R-QOC Colors: Green [Confirmed], Yellow [Stands], Red [Overturned]):

- ALCS-1 HP Umpire Chad Fairchild's out call on play at the plate is confirmed.

- ALCS-2 RF Umpire Chad Fairchild's home run call is confirmed to give Astros an early lead.

- ALCS-2 3B Umpire Jerry Meals' safe call is overturned to negate Gardner's triple.

- NLCS-1 2B Umpire Mike Winters' safe call on Bellinger's stolen base stands.

- NLCS-1 HP Umpire Lance Barksdale's collision violation no-call (out) is overturned; Maddon ejected.

- ALCS-3 HP Umpire Gary Cederstrom's HBP-no call stands as Replay cannot deduce ball's status.

- ALCS-3 1B Umpire Chris Guccione's safe call is overturned as infield single turns into a groundout.

- ALCS-4 1B Umpire Jerry Meals' out call is overturned, but Judge is still retired one play later.

- ALCS-4 2B Umpire Jim Reynolds' safe call is confirmed on Headley's late rallying base hit.

- NLCS-3 LF Umpire Eric Cooper's lodge call is confirmed as ball gets stuck in the Wrigley Field ivy.

- NLCS-4 1B Umpire Bill Welke's out call on attempted bunt single is confirmed in 5th inning.

- ALCS-6 HP Umpire Jim Reynolds' HBP-no call is overturned and Castro is awarded first base.

- ALCS-7 1B Umpire Hunter Wendelstedt's out call is confirmed at first base on pulled foot call.

Totals: 6 Confirmed + 2 Stands + 5 Overturned = 8/13 = .615 RAP.

NOTE There were 11 Replay Reviews during the 2016 LCS (4/11 = .364 RAP).

Labels:

Discussions

,

UEFL

,

Umpire Odds/Ends

Follow-Through (Backswing) Contact or Batter Interference?

Nationals catcher Matt Wieters campaigned for a backswing/follow-through contact (not interference) call after a throwing error on a passed ball third strike allowed Chicago to score a sixth run with two outs in the top of the 5th inning. Was HP Umpire Jerry Layne's no-call the correct ruling?

The Play: With two out and two on (R1, R2) in the top of the 5th inning of Game 5 of the Cubs-Nationals NLDS, Cubs batter Javier Baez swung and missed at a 0-2 slider from Nationals pitcher Max Scherzer, the pitched ball eluding Matt Wieters, who, in attempting to throw to first base to retire Baez on the uncaught third strike, overthrew his target for an unearned run-producing error. Replays indicate that Baez's bat incidentally made contact with Wieters on his follow-through.

Analysis: As we learned most recently, a batter becomes a runner on an uncaught third strike when two are out and may attempt to advance to first base before being put out.

Related Post: Yankees End Indians' ALDS on Uncaught Third Strike (10/11/17).

The question here is whether Baez's contact with Wieters constitutes backswing or follow-through contact (not interference). To answer this question, we first must cite the relevant regulation, which is found in Official Baseball Rule 6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment: "If a batter strikes at a ball and misses and swings so hard he carries the bat all the way around and, in the umpire’s judgment, unintentionally hits the catcher or the ball in back of him on the backswing, it shall be called a strike only (not interference). The ball will be dead, however, and no runner shall advance on the play."

With two strikes on the batter, a dead ball strike makes the count x-3, which means the back-swinging batter shall be ruled out on strikes, uncaught or not. See also the following 2016 Case Play regarding David Ortiz's backswing-aided strikeout (and double play).

Related Post: Case Play 2016-9 - A Backswing on Strike 3 [Solved] (8/26/16).

SIDEBAR: See above Case Play 2016-9 for rules differences between OBR, NCAA, and NFHS. In high school only, follow-through contact is interference. The technical lower-level lexicon has also established that "backswing contact" occurs pre-pitch whereas "follow-through" contact occurs post-pitch.

Seems simple, and at face value, this must be follow-through contact (not interference), right? Before we unequivocally declare, "case closed," let's read on.

6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment is merely an approved ruling or case play of OBR 6.03(a)(3), which states, "A batter is out for illegal action when—He interferes with the catcher’s fielding or throwing by stepping out of the batter’s box or making any other movement that hinders the catcher’s play at home base," and 6.03(a)(4), which states, "He throws his bat into fair or foul territory and hits a catcher (including the catcher's glove) and the catcher was attempting to catch a pitch with a runner(s) on base and/or the pitch was a third strike."

Plays at home base include the obvious (attempting to field a batted ball or bunt in front of home plate), attempting to tag out or throw out a runner or batter (e.g., as in a stolen base or pickoff), or another similar action that the catcher performs in the home plate area. For instance, when Big Papi's 2016 backswing contact with two strikes turned into an inning-ending double play with his catcher attempting to throw out a stealing runner, that would qualify as a play at home base.

SIDEBAR: We DO know, per the MLB Umpire Manual, that if the "catcher's initial throw directly retires a runner despite the infraction," the follow-through contact is disregarded, similar to batter interference in 6.03(c) proper. An "initial throw" implies a play that initiates at home base (e.g., a stolen base or pickoff throw); however, there was no "initial throw" nor were any Cubs retired on Thursday night's NLDS Game 5 play.

If 6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment falls hierarchically underneath 6.03(a)(3) proper, would it too be subject to the "catcher's play at home base" criterion? Refer to OBR's "Important Notes" section (page v) for more information about what Comments actually are: "The Playing Rules Committee, at its December 1977 meeting, voted to incorporate the Notes/Case Book/Comments section directly into the Official Baseball Rules at the appropriate places. Basically, the Case Book interprets or elaborates on the basic rules and in essence have the same effect as rules when applied to particular sections for which they are intended."

However, Rule 6.03(a)(4)—for which the Comment also applies—says nothing of a "play at home base," but does discuss a catcher attempting to catch a pitch with runners (or a third strike).

There are two compelling arguments to be made:

1) Because Wieters' passed ball occurred prior to Baez's unintentional follow-through contact, there is no cause for a call, as Baez's backswing had no relation to Wieters' play at home base; Wieters' inaccurate throw to first base was made from the warning track just feet from the backstop—a difficult throw for any fielder to make. No call is the correct call... But wait, there's more!

2) Because follow-through contact is specifically "not interference," it is not subject to the same dose of umpire discretion or judgment for how severe the violation was relative to hindrance—if there was any follow-through contact between bat and catcher (or ball), it must be ruled as such. For all we know, Baez's bat brush of Wieters' mask induced a minor head injury that in turn caused the poor throw. Nonetheless, that isn't an umpire's concern. Because OBR 6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment simply states "If a batter...unintentionally hits the catcher...on the backswing, it shall be called a strike only (not interference). The ball will be dead," the call must be made regardless of severity when any instance of follow-through contact occurs. Recall 6.03(a) is about "illegal action," and not about "interference." Only 6.03(a)(3) concerns interference.

Furthermore, if Comments, which come from Case Book, "have the same effect as rules when applied to particular sections for which they are intended," then, hierarchically, 6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment carries precisely the same weight as 6.03(a)(3) and 6.03(a)(4) proper, meaning that the follow-through contact provision logically stands on its own, without reference to 6.03(a)(3)'s remarks concerning interference at "home base." For instance, 6.03(a) also states "a batter is out for illegal action," yet there is no question that the batter is not out when follow-through contact occurs with less than two strikes. Thus, by the same logical token, 6.03(a)(3)'s "play at home base" phrase should similarly have no bearing on 6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment concerning follow-through contact, especially when 6.03(a)(4) makes no reference to a play at home base other than attempting to catch a pitch. By contrast, one could argue that although the pitch was already uncaught by the time of the contact, if the ball had caromed out of play on the passed ball, the award would still be one base. Why? Because it was still a pitched ball.

SIDEBAR: Just for fun, the next batter, Tommy La Stella, reached first base due to catcher's interference on Wieters, a rare back-to-back sequence of E2's (with a passed ball to boot).

Thus, the follow-through contact occurred while the ball was still a "pitched ball," so the pitched ball provision of 6.03(a)(4) is still relevant (playing devil's advocate). It is not interference, but an illegal action for which the batter is out (on the dead ball third strike). Henceforth, the logic covers both trains of thought (that 6.03(a)(3) or (4) matters or that 6.03(a)(3) or (4) does not matter). In conclusion, no call is the incorrect call.

Video as follows:

|

| Baez's bat makes contact with Wieters' mask. |

Analysis: As we learned most recently, a batter becomes a runner on an uncaught third strike when two are out and may attempt to advance to first base before being put out.

Related Post: Yankees End Indians' ALDS on Uncaught Third Strike (10/11/17).

The question here is whether Baez's contact with Wieters constitutes backswing or follow-through contact (not interference). To answer this question, we first must cite the relevant regulation, which is found in Official Baseball Rule 6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment: "If a batter strikes at a ball and misses and swings so hard he carries the bat all the way around and, in the umpire’s judgment, unintentionally hits the catcher or the ball in back of him on the backswing, it shall be called a strike only (not interference). The ball will be dead, however, and no runner shall advance on the play."

With two strikes on the batter, a dead ball strike makes the count x-3, which means the back-swinging batter shall be ruled out on strikes, uncaught or not. See also the following 2016 Case Play regarding David Ortiz's backswing-aided strikeout (and double play).

Related Post: Case Play 2016-9 - A Backswing on Strike 3 [Solved] (8/26/16).

SIDEBAR: See above Case Play 2016-9 for rules differences between OBR, NCAA, and NFHS. In high school only, follow-through contact is interference. The technical lower-level lexicon has also established that "backswing contact" occurs pre-pitch whereas "follow-through" contact occurs post-pitch.

|

| Wieters campaigns to Layne for a call. |

6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment is merely an approved ruling or case play of OBR 6.03(a)(3), which states, "A batter is out for illegal action when—He interferes with the catcher’s fielding or throwing by stepping out of the batter’s box or making any other movement that hinders the catcher’s play at home base," and 6.03(a)(4), which states, "He throws his bat into fair or foul territory and hits a catcher (including the catcher's glove) and the catcher was attempting to catch a pitch with a runner(s) on base and/or the pitch was a third strike."

Plays at home base include the obvious (attempting to field a batted ball or bunt in front of home plate), attempting to tag out or throw out a runner or batter (e.g., as in a stolen base or pickoff), or another similar action that the catcher performs in the home plate area. For instance, when Big Papi's 2016 backswing contact with two strikes turned into an inning-ending double play with his catcher attempting to throw out a stealing runner, that would qualify as a play at home base.

SIDEBAR: We DO know, per the MLB Umpire Manual, that if the "catcher's initial throw directly retires a runner despite the infraction," the follow-through contact is disregarded, similar to batter interference in 6.03(c) proper. An "initial throw" implies a play that initiates at home base (e.g., a stolen base or pickoff throw); however, there was no "initial throw" nor were any Cubs retired on Thursday night's NLDS Game 5 play.

|

| Wieters demonstrates the bat contact. |

However, Rule 6.03(a)(4)—for which the Comment also applies—says nothing of a "play at home base," but does discuss a catcher attempting to catch a pitch with runners (or a third strike).

There are two compelling arguments to be made:

1) Because Wieters' passed ball occurred prior to Baez's unintentional follow-through contact, there is no cause for a call, as Baez's backswing had no relation to Wieters' play at home base; Wieters' inaccurate throw to first base was made from the warning track just feet from the backstop—a difficult throw for any fielder to make. No call is the correct call... But wait, there's more!

2) Because follow-through contact is specifically "not interference," it is not subject to the same dose of umpire discretion or judgment for how severe the violation was relative to hindrance—if there was any follow-through contact between bat and catcher (or ball), it must be ruled as such. For all we know, Baez's bat brush of Wieters' mask induced a minor head injury that in turn caused the poor throw. Nonetheless, that isn't an umpire's concern. Because OBR 6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment simply states "If a batter...unintentionally hits the catcher...on the backswing, it shall be called a strike only (not interference). The ball will be dead," the call must be made regardless of severity when any instance of follow-through contact occurs. Recall 6.03(a) is about "illegal action," and not about "interference." Only 6.03(a)(3) concerns interference.

Furthermore, if Comments, which come from Case Book, "have the same effect as rules when applied to particular sections for which they are intended," then, hierarchically, 6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment carries precisely the same weight as 6.03(a)(3) and 6.03(a)(4) proper, meaning that the follow-through contact provision logically stands on its own, without reference to 6.03(a)(3)'s remarks concerning interference at "home base." For instance, 6.03(a) also states "a batter is out for illegal action," yet there is no question that the batter is not out when follow-through contact occurs with less than two strikes. Thus, by the same logical token, 6.03(a)(3)'s "play at home base" phrase should similarly have no bearing on 6.03(a)(3) & (4) Comment concerning follow-through contact, especially when 6.03(a)(4) makes no reference to a play at home base other than attempting to catch a pitch. By contrast, one could argue that although the pitch was already uncaught by the time of the contact, if the ball had caromed out of play on the passed ball, the award would still be one base. Why? Because it was still a pitched ball.

SIDEBAR: Just for fun, the next batter, Tommy La Stella, reached first base due to catcher's interference on Wieters, a rare back-to-back sequence of E2's (with a passed ball to boot).

Thus, the follow-through contact occurred while the ball was still a "pitched ball," so the pitched ball provision of 6.03(a)(4) is still relevant (playing devil's advocate). It is not interference, but an illegal action for which the batter is out (on the dead ball third strike). Henceforth, the logic covers both trains of thought (that 6.03(a)(3) or (4) matters or that 6.03(a)(3) or (4) does not matter). In conclusion, no call is the incorrect call.

Video as follows:

Labels:

Articles

,

Ask the UEFL

,

Jerry Layne

,

Rule 6.03

,

Rules Review

,

UEFL

,

Umpire Odds/Ends

,

Video Analysis

Thursday, October 12, 2017

2017 League Championship Series Umpires Roster

The 2017 AL and NL League Championship Series umpire roster is now available, listed by crew assignment. The Replay Official for the LCS and World Series serves in MLBAM's New York-based Replay Operations Center for Games One and Two of the series, before joining the on-field crew for Games Three through Seven. The home plate umpire for Game One of the series correspondingly serves as the Replay Official for Games Three through Seven.

American League Championship Series (New York Yankees @ Houston Astros)

HP: Chad Fairchild `1st LCS` [Game 1 Plate] [Replay Review Games 3-7]

1B: Hunter Wendelstedt [Game 2 Plate]

2B: Gary Cederstrom* -wc [Game 3 Plate]

3B: Chris Guccione -wc [Game 4 Plate]

LF: Jerry Meals* [Game 5 Plate]

RF: Jim Reynolds -wc [Game 6 Plate]

Replay Review: Mark Carlson -wc [Game 7 Plate] [On-Field Games 3-7]

National League Championship Series (Chicago Cubs @ Los Angeles Dodgers)

HP: Lance Barksdale `1st LCS` -wc [Game 1 Plate] [Replay Review Games 3-7]

1B: Todd Tichenor `1st LCS` [Game 2 Plate]

2B: Mike Winters* -wc [Game 3 Plate]

3B: Jim Wolf [Game 4 Plate]

LF: Bill Welke -wc-replay [Game 5 Plate]

RF: Alfonso Marquez -wc [Game 6 Plate]

Replay Review: Eric Cooper -wc [Game 7 Plate] [On-Field Games 3-7]

Replay Assistant, American and National League Championship Series: Mike Muchlinski.

Bold text denotes Game/Series Crew Chief, * denotes regular season Crew Chief, ^1st^ denotes first postseason assignment; `1st LCS` denotes first League Championship Series assignment; -wc denotes an appearance during the 2017 Wild Card Game round. Per UEFL Rule 4-3-c, all umpires selected to appear in the League Championship Series shall receive three bonus points for this appearance; crew chiefs shall receive one additional bonus point for this role (four points total). Officials assigned to replay review (without an on-field role) only do not receive points for this role.

American League Championship Series (New York Yankees @ Houston Astros)

HP: Chad Fairchild `1st LCS` [Game 1 Plate] [Replay Review Games 3-7]

1B: Hunter Wendelstedt [Game 2 Plate]

2B: Gary Cederstrom* -wc [Game 3 Plate]

3B: Chris Guccione -wc [Game 4 Plate]

LF: Jerry Meals* [Game 5 Plate]

RF: Jim Reynolds -wc [Game 6 Plate]

Replay Review: Mark Carlson -wc [Game 7 Plate] [On-Field Games 3-7]

National League Championship Series (Chicago Cubs @ Los Angeles Dodgers)

HP: Lance Barksdale `1st LCS` -wc [Game 1 Plate] [Replay Review Games 3-7]

1B: Todd Tichenor `1st LCS` [Game 2 Plate]

2B: Mike Winters* -wc [Game 3 Plate]

3B: Jim Wolf [Game 4 Plate]

LF: Bill Welke -wc-replay [Game 5 Plate]

RF: Alfonso Marquez -wc [Game 6 Plate]

Replay Review: Eric Cooper -wc [Game 7 Plate] [On-Field Games 3-7]

Replay Assistant, American and National League Championship Series: Mike Muchlinski.

Bold text denotes Game/Series Crew Chief, * denotes regular season Crew Chief, ^1st^ denotes first postseason assignment; `1st LCS` denotes first League Championship Series assignment; -wc denotes an appearance during the 2017 Wild Card Game round. Per UEFL Rule 4-3-c, all umpires selected to appear in the League Championship Series shall receive three bonus points for this appearance; crew chiefs shall receive one additional bonus point for this role (four points total). Officials assigned to replay review (without an on-field role) only do not receive points for this role.

Labels:

Rosters

,

UEFL

,

Umpire Odds/Ends

Yankees End Indians' ALDS on Uncaught Third Strike

How Cleveland's 2017 ALDS experience ended on an uncaught third strike that HP Umpire Jeff Nelson seemingly made no ruling on inspired some post-series questions by baseball rule aficionados and fans alike.

In today's edition of Ask the UEFL, we review just how a game—not to mention a postseason series—concluded with such a play that seemed to go undetected by personnel from both teams, and how common sense and fair play prevailed at Progressive Field during a sequence that could have turned into a repeat of Game Two of the 2005 American League Championship Series...had only the batter noticed.

The Play: With two out and one on (R2) in the bottom of the 9th inning of Game 5 of the American League Division Series, with the Yankees leading, 5-2, NYY closer Aroldis Chapman threw a 1-2 fastball to Indians batter Austin Jackson for a called third strike. Replays indicate that Chapman's 1-2 fastball to Jackson, correctly called a strike by HP Umpire Nelson (px -.327, pz 3.461 [sz_top 3.411 / sz_top_true 3.534]), fell out of catcher Gary Sanchez's mitt and onto the ground, upon which Sanchez picked up the baseball and jogged toward the pitcher's mound to celebrate as batter Jackson and umpire Nelson remained near home plate, Sanchez ultimately placing the ball into his back pocket as Jackson argued with Nelson.

Analysis and Relevant Rules: First and foremost, we shall establish batter Jackson's status as a runner by citing Official Baseball Rule 5.05(a)(2), which states, "The batter becomes a runner when—the third strike called by the umpire is not caught, providing (1) first base is unoccupied, or (2) first base is occupied with two out."

Sidebar: A common misconception is that the batter must swing at the uncaught third strike in order to be eligible to run to first base, but this is not true: the pitch must only be a third strike not caught, with first base unoccupied or two out, and a live ball (e.g., a foul bunt is a dead ball, so the batter is out). For instance, if, with two out and first base occupied, a called third strike is uncaught, the batter may run to first base and if he beats the catcher's throw or tag, he is safe. Naturally, if the baserunner from first base fails to run to second ahead of the throw (now that he is forced to do so by virtue of the batter becoming a runner), then the runner will be out when the base or he is tagged, and the on-deck batter (or his substitute) will lead off the following inning.

Rule 5.04(b)(4) covers a plethora of base awards for when a live ball is batted, thrown, or pitched out of play ("each runner including the batter-runner may, without liability to be put out, advance"), with 5.04(b)(4)(G) proving most relevant to this case: "Two bases when, with no spectators on the playing field, a thrown ball goes into the stands, or into a bench."

But that is about a ball exiting the playing field, not entering a player's uniform. Cue Rule 5.06(c)(7): "The ball becomes dead and runners advance one base, or return to their bases, without liability to be put out, when...A pitched ball lodges in the umpire’s or catcher’s mask or paraphernalia, and remains out of play, runners advance one base."

Is the pocket out of play? We answered this question in 2016 when Jose Altuve placed a ball in his back pocket as part of a mock hidden ball trick: Yes, the ball is out of play when it enters a player's uniform pocket. Just as Altuve would be prohibited from tagging out a runner, so too would Sanchez.

Related Post: Case Play 2016-2, Ball in the Pocket [Solved] (4/13/16)

For the precise base award, let's dig a little deeper into the Approved Ruling: "If, however, the pitched or thrown ball goes through or by the catcher or through the fielder, and remains on the playing field, and is subsequently kicked or deflected into the dugout, stands or other area where the ball is dead, the awarding of bases shall be two bases from position of runners at the time of the pitch or throw."

This, essentially, is what we have here: a defensive player taking a live ball out of play. The rulebook award is two bases from the time of Sanchez's "throw," as his was a deliberate act of putting the ball into his uniform (and thus, out of play). The MLB Umpire Manual agrees: "If, in the judgment of the umpires, a fielder intentionally kicks or deflects any batted or thrown ball out of play, the award is two bases from the time the ball was kicked or deflected." The ball is no longer a "pitched ball" when the fielder gains complete possession of it. By tucking it into his pocket, Sanchez "threw" the ball out of play.

This odd scenario only could realistically transpire (conceivably) on a game-ending third strike, which brings us to two more relevant rules:

Rule 5.05(a)(2) Comment states, "A batter who does not realize his situation on a third strike not caught, and who is not in the process of running to first base, shall be declared out once he leaves the dirt circle surrounding home plate."

Rule 5.06(c)(7) Comment states, in part, "If a pitched ball lodges in the umpire’s or catcher’s mask or paraphernalia, and remains out of play, on the third strike or fourth ball, then the batter is entitled to first base and all runners advance one base."

Because catcher Sanchez placed the ball into his pocket and out of play before batter-runner Jackson left the dirt circle surrounding home plate, by rule, Jackson is entitled to reach base safely.

However, it is wise to consider the General Instructions to Umpires in Rule 8.00: "It is often a trying position which requires the exercise of much patience and good judgment."

In 2016, regarding the Altuve play, we wrote, "Take stock of the situation at the moment the ball becomes dead: The runner is standing on second base not intending to advance; accordingly, the proper call is to place the runner on second base and resume play with one out and one on."

Similarly, although it might be the rules-correct call to disrupt New York's celebration and award two bases to a Cleveland batter (and runner) not expecting to continue the game, the patience to allow the entire play to develop before deciding whether to call the play dead and to impose awards or penalties may lead to better judgment when it becomes apparent that the batter has given himself up pursuant to the spirit of Rule 5.05(a)(2) Comment regarding dirt circle departure.

HOWEVER: Unless Nelson ruled that Sanchez dropped the ball during the transfer to his throwing hand after having caught it (in which case the batter was already out), it would have been wise to keep an eye on the play—and batter-runner Jackson—until Jackson exited the dirt circle: even though we speak of common sense and fair play in regards to Jackson giving himself up relative to Sanchez pocketing the ball, Jackson is still not technically out—and should be considered an active runner—until he walks away from the dirt circle or shows no effort to advance. Whether you want to informally deem this a potentially delayed dead ball, or whatever else have you, it still bears mentioning that Jackson determined his own destiny following the uncaught third strike, and had a right to make up his mind until he left the dirt circle. Assuming, of course, that Nelson didn't rule the third strike caught and bobbled on the transfer.

Had Jackson began running to first base as Nelson was walking off the field—with the ball in catcher Sanchez's pocket and Jackson still adjacent to the right-handed batter's box—the common sense and fair play call would then have been to award Jackson his bases, as the batter-runner is entitled to attempt to advance on a two-out uncaught third strike until he is either put out or puts himself out by virtue of leaving the dirt circle. Fortunately for New York, and perhaps Nelson, too, Jackson did not appear to realize his situation, and eventually did leave the dirt circle toward his dugout. I know I've mentioned the advantage of having a first base, as opposed to third base, dugout before...

History: If the hypothetical scenario described above sounds familiar, it should, because it happened in the postseason before. In 2005, White Sox batter AJ Pierzynski slightly delayed his run to first base on an uncaught third strike during the 2005 Angels-White Sox ALCS. The stakes were quite huge here—the game was tied in the 9th—and Chicago ultimately won the contest, due in great part to Pierzynski's post-strikeout maneuver. Though HP Umpire Doug Eddings' uncaught third strike mechanic was hotly debated after the contest—as was the issue of whether the ball actually touched the ground—Eddings' final ruling of an uncaught third strike prevailed, in great part because he stayed with the play.

Related Link: Pierzynski reaches first base on strikeout after Angels assume an out (10/12/05)

Video as follows:

|

| Yankees celebrate a series win over Cleveland. |

The Play: With two out and one on (R2) in the bottom of the 9th inning of Game 5 of the American League Division Series, with the Yankees leading, 5-2, NYY closer Aroldis Chapman threw a 1-2 fastball to Indians batter Austin Jackson for a called third strike. Replays indicate that Chapman's 1-2 fastball to Jackson, correctly called a strike by HP Umpire Nelson (px -.327, pz 3.461 [sz_top 3.411 / sz_top_true 3.534]), fell out of catcher Gary Sanchez's mitt and onto the ground, upon which Sanchez picked up the baseball and jogged toward the pitcher's mound to celebrate as batter Jackson and umpire Nelson remained near home plate, Sanchez ultimately placing the ball into his back pocket as Jackson argued with Nelson.

Analysis and Relevant Rules: First and foremost, we shall establish batter Jackson's status as a runner by citing Official Baseball Rule 5.05(a)(2), which states, "The batter becomes a runner when—the third strike called by the umpire is not caught, providing (1) first base is unoccupied, or (2) first base is occupied with two out."

Sidebar: A common misconception is that the batter must swing at the uncaught third strike in order to be eligible to run to first base, but this is not true: the pitch must only be a third strike not caught, with first base unoccupied or two out, and a live ball (e.g., a foul bunt is a dead ball, so the batter is out). For instance, if, with two out and first base occupied, a called third strike is uncaught, the batter may run to first base and if he beats the catcher's throw or tag, he is safe. Naturally, if the baserunner from first base fails to run to second ahead of the throw (now that he is forced to do so by virtue of the batter becoming a runner), then the runner will be out when the base or he is tagged, and the on-deck batter (or his substitute) will lead off the following inning.

|

| Nelson views Jackson as the ball is pocketed. |

But that is about a ball exiting the playing field, not entering a player's uniform. Cue Rule 5.06(c)(7): "The ball becomes dead and runners advance one base, or return to their bases, without liability to be put out, when...A pitched ball lodges in the umpire’s or catcher’s mask or paraphernalia, and remains out of play, runners advance one base."

Is the pocket out of play? We answered this question in 2016 when Jose Altuve placed a ball in his back pocket as part of a mock hidden ball trick: Yes, the ball is out of play when it enters a player's uniform pocket. Just as Altuve would be prohibited from tagging out a runner, so too would Sanchez.

Related Post: Case Play 2016-2, Ball in the Pocket [Solved] (4/13/16)

|

| Jose Altuve put a ball in his pocket in 2016. |

This, essentially, is what we have here: a defensive player taking a live ball out of play. The rulebook award is two bases from the time of Sanchez's "throw," as his was a deliberate act of putting the ball into his uniform (and thus, out of play). The MLB Umpire Manual agrees: "If, in the judgment of the umpires, a fielder intentionally kicks or deflects any batted or thrown ball out of play, the award is two bases from the time the ball was kicked or deflected." The ball is no longer a "pitched ball" when the fielder gains complete possession of it. By tucking it into his pocket, Sanchez "threw" the ball out of play.

This odd scenario only could realistically transpire (conceivably) on a game-ending third strike, which brings us to two more relevant rules:

Rule 5.05(a)(2) Comment states, "A batter who does not realize his situation on a third strike not caught, and who is not in the process of running to first base, shall be declared out once he leaves the dirt circle surrounding home plate."

Rule 5.06(c)(7) Comment states, in part, "If a pitched ball lodges in the umpire’s or catcher’s mask or paraphernalia, and remains out of play, on the third strike or fourth ball, then the batter is entitled to first base and all runners advance one base."

Because catcher Sanchez placed the ball into his pocket and out of play before batter-runner Jackson left the dirt circle surrounding home plate, by rule, Jackson is entitled to reach base safely.

However, it is wise to consider the General Instructions to Umpires in Rule 8.00: "It is often a trying position which requires the exercise of much patience and good judgment."

In 2016, regarding the Altuve play, we wrote, "Take stock of the situation at the moment the ball becomes dead: The runner is standing on second base not intending to advance; accordingly, the proper call is to place the runner on second base and resume play with one out and one on."

|

| By rule, Jackson is still not out. |

HOWEVER: Unless Nelson ruled that Sanchez dropped the ball during the transfer to his throwing hand after having caught it (in which case the batter was already out), it would have been wise to keep an eye on the play—and batter-runner Jackson—until Jackson exited the dirt circle: even though we speak of common sense and fair play in regards to Jackson giving himself up relative to Sanchez pocketing the ball, Jackson is still not technically out—and should be considered an active runner—until he walks away from the dirt circle or shows no effort to advance. Whether you want to informally deem this a potentially delayed dead ball, or whatever else have you, it still bears mentioning that Jackson determined his own destiny following the uncaught third strike, and had a right to make up his mind until he left the dirt circle. Assuming, of course, that Nelson didn't rule the third strike caught and bobbled on the transfer.

|

| AJ runs to first as the Angels leave the field. |

History: If the hypothetical scenario described above sounds familiar, it should, because it happened in the postseason before. In 2005, White Sox batter AJ Pierzynski slightly delayed his run to first base on an uncaught third strike during the 2005 Angels-White Sox ALCS. The stakes were quite huge here—the game was tied in the 9th—and Chicago ultimately won the contest, due in great part to Pierzynski's post-strikeout maneuver. Though HP Umpire Doug Eddings' uncaught third strike mechanic was hotly debated after the contest—as was the issue of whether the ball actually touched the ground—Eddings' final ruling of an uncaught third strike prevailed, in great part because he stayed with the play.

Related Link: Pierzynski reaches first base on strikeout after Angels assume an out (10/12/05)

Video as follows:

Labels:

Articles

,

Ask the UEFL

,

Jeff Nelson

,

Rule 5.05

,

Rule 5.06

,

Rule 8.00 [General Instructions]

,

Rules Review

,

UEFL

,

Umpire Odds/Ends

,

Video Analysis

Tuesday, October 10, 2017

Let's Talk - Mental Health in an Abusive Environment

Lin's Call: Let's talk about mental health in officiating. With umpire and referee abuse continuing to plague the sports world, chances are the average official has encountered more than one castigating coach or persecuting player. Combine that with a cocktail of a pre-existing or developing ailment, and it may feel overwhelming. October 10 is World Mental Health Day, a day for global mental health education, awareness, and advocacy.

Unfortunately, mental health resources specific to the unique challenges, aggravations, and circumstances of officiating are limited in nature. Very few careers—and virtually no avocations—carry as much regular vituperation as officiating.

In this article, we'll attempt to introduce the most common wellness tactics that relate to officiating: namely, dealing with verbal abuse and its associated environment.

In late June, off-duty MLB Umpire John Tumpane helped save a woman's life on the Roberto Clemente Bridge after she seemed poised to jump into the Allegheny River below. Among the woman's chief concerns were, "no one wants to help me," "I'm better off on this side," and "You don't care about me."

Among Tumpane's remarks were, "Let's talk this out," "We want you to get better," and "I'll never forget you."

The following discussion pertains largely to mental health challenges which occur before, during, or after an athletic contest. Sometimes, this "after" can be hours. Sometimes, it might even be days or weeks. If you or someone you know is in crisis or having thoughts of suicide or hopelessness, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. You can also chat online with a trained operator.

Officiating can be an extremely rewarding experience, and, for the most part, the various sports' participants exemplify the values of good sportsmanship that allow for the furtherance of these positive feelings.

While acknowledging philosopher John Locke's belief that in the state of nature, people are generally peaceful, good, and pleasant, we also dip into Thomas Hobbes' famous line about life: "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

The more games one officiates, the more likely one is to encounter the classical Hobbesian bad actor. A 2012 University of Toronto study found that 92% of hockey referee respondents indicated they had been the recipients of aggression or anger on the ice, while 55% officiated contests that "ran out of control." Nonetheless, 80% of referees and linesmen indicated that they still enjoyed officiating.

Why abusers do it: Sports, of course, create an artificial conflict (e.g., two teams compete to win) that departs from the nature state and places pressure on participants. This creates an atmosphere ripe for the blame game (umpire scapegoating). In short, participants who blame officials shirk personal responsibility for an undesirable outcome because accepting the result is too personally unpleasant. In doing so, scapegoats project negative emotions onto others in a Level 2, or immature, defense mechanism, similar to the defense of displacement, whose rationale is similar. Sometimes, abusers feel so pinned into a corner when something doesn't go their way—generally when they feel that failing to win might cost them a job or coveted role—that they lash out at anyone who will listen...they might even hope to convince their employer, coach, or fans that the umpire is to blame for their poor job performance. That's right, mismanagement of the Miami Marlins resulted in Mark Wegner ejecting Mike Redmond over a fairly obvious interference call in 2013. Nonetheless, the blame-game display wasn't enough to save Redmond's job, and he was eventually dismissed in May 2015 after racking up five ejections during the 2014 season. In modern ball, Brad Ausmus seems headed down a similarly ominous path.

Related Post: Gil's Call - The Blame Game (Umpire Scapegoating).

In Plain Terms: When a player or coach abuses an official, the abuse is seldom about the official being abused. Yes, as absurd as it may sound, personal insults of an official generally have nothing to do with the official personally—most players and coaches don't know their officials all that well to begin with. The act often concerns some underlying issue within the person committing the abuse and may represent a personal struggle that person has with authority, lack of control, or accepting a result in conflict with one's own desires. Some people simply don't like being told "no" and rather than accept the answer, they attack the rejector. No doesn't always mean no to some people. Others may seek to maintain a false sense of bravado by blaming the referee for a poor performance that might otherwise hurt their self-image (and public persona).

In Plainer Terms: It's about the disturbed state of the participant, not about the official.

Defining Abuse: Verbal or physical abuse of officials can comprise a wide variety of bullying tactics and unwanted aggressive behavior that might include force, a threat, intimidation, or attempt to dominate. It can be a player who hurls personal insults, a coach who threatens to call one's assigner or supervisor, to throwing equipment, kicking dirt, threatening remarks such as "I'll see you in the parking lot," and anything in between.

How to Deal with Abuse - Outward Action: The first response is to set boundaries and put a stop to the abuse. Nearly all sports' rules books delineate "abuse of official" as an unsportsmanlike act that merits some measure of discipline. Whether it's a formal warning, minor penalty, unsportsmanlike foul, technical foul, misconduct, disqualification, ejection, or game misconduct, the various rulebooks all establish that abuse is unacceptable. Severe or repeated abuse may call for removal from the game. To ensure physical safety (in the event of intimidation or threats), it might be necessary to consult game management or even call the police. Severe physical abuse, assault, or battery of officials always calls for an arrest.

Related Link: Ejections - What and Wherefore? Standards for Removal from the Game.

As I previously wrote, officials exist to enforce the rules so that each team has a chance to thrive in a fair and balanced environment. An unsporting or abusive coach who engages in tactics meant to tip the scales to as much as 51% to 49% has committed an unsporting act of attempting to change the rules or their enforcement so as to create an unfair advantage for his/her team. Some participants simply don't care how they win, as long as they do win, in a "the end always justifies the means" approach. Some are less nefarious in their intent, while others simply want to see how far they can push their luck. Officials exist to ensure that "the means" stay within the confines of the rules.

Related Post: Crew Consultation - Importance of the Call on the Field.

Furthermore, we can all take a page from Tumpane's book and apply it to the ballpark or arena, striving to be better crew-mates through praise, encouragement, and actively striving to strengthen the bonds of kinship and camaraderie both on and off the field. Before, during, and after a game, officials are often other officials' only friends.

How to Deal with Abuse - Inward Action (Self-Talk): Although the aforementioned logic might help to depersonalize the abuse, regaining control of one's feelings during an abusive episode is another story entirely. Bullies are not pleasant no matter how wrong they are, and there is a real psychological toll on the official that goes farther than the logical brain.

Prior to conflict, learning the basic principles of self control—the ability to subdue impulses in order to achieve longer-term goals—will help later on when an incident does occur. In an abuse situation, the impulse is the self-critical emotional one, while the longer-term goal is simply to exit the situation in a healthy mental state.

Depersonalization—becoming a detached observer of your self or situation—when employed sparingly and strategically during an abusive episode may provide even further perspective to sterilize the abuse. Just be sure the strategy is a conscious short-term decision and not a routine way of conducting business. Dissociation is one of Vaillant's neurotic defense mechanisms, which, when taken to an extreme, is not healthy. HOWEVER, the humor that may result is a healthier strategy.

Understanding the presupposition that the abuser's claim of bias is wrong, that the discipline being imposed is a just step called for in the standard enforcement of a rule, or that the abuser is just upset because a call didn't go his/her way are all potential self-talk actions that could take the wind out of an abusive comment or action's sails.

Like any skill, willpower (the ability to exert self-control) becomes stronger with practice, so, yes, something as silly as sticking to a diet or finishing a work assignment instead of watching TV increases the willpower skill. Working on willpower helps to mediate not just impulse, but other emotions, which comes in handy during an abuse situation by giving the official the upper hand in sitting with, and then parsing through, unpleasant emotions. Mindfulness, meditation, and similar techniques also have the opportunity to contribute to this presence skill.

Speaking of presence, staying in the present after an unpleasant in-game incident helps recognize, regroup, and refocus (Referee briefly touched on the Three R's in September). Officiating the balance of the game offers a tremendous incentive to walk away from the emotionally charged abuse situation and direct energy back toward something that the official can do with confidence. Recognize and acknowledge what has happened and the mind-body's reaction to it, regroup by putting things in their proper perspective, and refocus for the task at hand (continuing the game). Confidence is a tremendous attribute toward combating a bully's attempt at lowering one's self esteem, and returning to officiate a game after the abusive incident builds confidence.

Post-Abuse Abuse: After an official has disciplined a participant for abuse, that participant is likely to get even more abusive. For instance, when officials are physically struck by players or coaches, this violent crime is significantly more likely to occur after the guilty participant has already been ejected from the game. First, the offender is embarrassed for having been called on his/her abusive behavior. Second, the offender thinks "what have I got to lose?" after being disciplined, which is further reinforced by the popular broadcasting term, "get your money's worth." Kill the Umpire culture certainly doesn't help.

Related Post: Did Detroit Throw at Umpire Wolcott? A Visual Analysis (9/14/17).

If the Abuse Caused the Game to End (or happened after the final out/horn): If the game has concluded or been abandoned, it might not be possible to refocus on officiating. A forfeit due to unsporting conduct in particular is an unusual circumstance. If possible, postgame the incident with a crew mate. Talking through the issue is another healthy coping mechanism that will greatly help reground the recipient of abuse. Adding just one other outside voice to combat the abuser's is a powerful tool in providing perspective, and strong bonds within a crew provide the necessary camaraderie to further combat "war story" bullies. Give extraordinarily insignificant credence to the bully's outlandish statements of fantasy.

The Four Types of Game Participants: There are generally three or four types of players and coaches, relative to officiating, and participants can bounce between neighboring types during a game, or from game-to-game:

Allies: These players and coaches demonstrate a desire to create positive working relationships with officials. They'll say hi at the beginning and they'll look to shake hands or wave at the end. Yes, there might be disagreements—even loud ones—but allies are always respectful and generally proactive in trying to dissuade teammates from committing unsporting acts. Always remember, though, they are not the same as friends (though a select few might actually be a friend). They are game participants who happen to exhibit the attributes of allies. At the end of the day, naturally, they would prefer their team prevail, whereas our officiating friends care not one whit which wing wins.

Neutrals: Comprising the bulk of participants, these persons don't go out of their way to build much rapport, but neither will they antagonize officials. Neutrals generally don't interact much with referees and umpires, largely because they are either concentrating on their own game or simply don't bother themselves with officiating matters, which they see as outside of their locus of control. They might exhibit traits both congenial and challenging, though not too notable in either direction.

Adversaries: Some players and coaches thrive off building an adversarial relationship with nearly everyone on the playing field, including officials. For some, a "the world is against me" attitude has helped them succeed before, and, through positive reinforcement, they have adopted the mantra as their playing attitude. These participants may push buttons and attempt to find where the boundary line is, albeit without much malice.

Abusers: These are playground bullies on a sports field. Harassment is routine, yelling is generally constant or often simmering, and the worst thing about it is that the abusive behavior is durable, largely because it has worked for the abuser in the past through a lack of consequences or even a reward (or perceived positive result). Though an official must treat all game participants equally within their class of participation (e.g., more tolerance is shown to a head coach than an assistant coach, but equal tolerance should be extended to both teams' head coaches), an abuser will generally burn an official's fuse a lot quicker than the other three participant types—combined. Don't be afraid to discipline that which is abusive.

Although getting away from an abuser may temporarily halt the potentially unsporting behavior—and it is appealing to keep the ejection- or technical-gun in its holster—chances are that a future call that goes against the abuser's team will be met with an episode of greater harassment. Remember, intimidation or being made to feel guilty is a tactic of abuse and must be dealt with assertively. Bullies thrive on passive victims' behavior. Reassurance from an assignor or league supervisor might greatly help an official deal with such a situation, allowing the official to feel confident that the league will back his/her stance.

If the league administration won't support you, the first step is to galvanize the troops: all of the league's officials must band together to demand fair and humane treatment, including support for enforcing the rules of the sport one is expected to officiate—it took all of one day for MLB to agree to meet with the World Umpires Association after WUA announced its white wristband protest. If this is not possible or the administration continues to balk, then the league's respect for its officials is far too low to merit quality officiating. Either walk away and regain your power or acknowledge that the league wants the game called a certain way, and if this is acceptable to you, continue to work, knowing that you may be dealing with a league whose rules are compromised. You may have to adjust expectations and learn to officiate "down" to the league's level.

Related Post: WUA-MLB Relations Deteriorate with New Umpire Protest (8/19/17).

Related Post: WUA Secures Commissioner Meeting, Suspends Protest (8/20/17).

How to Prevent, Stop, or Curtail Abuse: We don't ordinarily discuss "how to prevent abuse" because, in society-at-large, we consider it largely taboo to place the burden of responsibility for preventing abuse on the victim: after all, the perpetrator shouldn't commit the abuse to begin with. No means no.

Except when, again, someone doesn't accept no as an answer.

In officiating, it is an unfortunate reality that abuse is a more-than-regular occurrence, and, fair or not, we have to arm ourselves with tools to prevent potential bullies from turning abusive. Sometimes, we put up with unpleasant behavior to prevent larger displays of abuse (similar to slowly releasing a steam valve so as to relieve pressure within a pipe so as to prevent the pipe from bursting), and other times we must warn or use a "stop sign" to reseal the metal.

Tact, composure, and demeanor go a long way in officiating. Confidence in game-calling—or even faux confidence—tells potential abusers that one is sure of the calls being made, and not susceptible to intimidation techniques. Every so often, humor helps disarm a would-be combatant.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Confidence doesn't necessarily mean overselling every single call. Joe West might have one of the least enthusiastic strike three calls in the major leagues, yet there is no question as to his confidence in calling a ballgame. Rather, it's West's deliberate demeanor that conveys his assuredness ("You cannot back down as an umpire. You can't be scared as an umpire. You have to do what's right").

West explained a lesson taught to him by Hall of Famer Doug Harvey: "Don't let them ruin your day. You're having a good day. If they give you trouble to kick them out, kick them out. But don't let it ruin your day," a similar message to Tumpane's words after the bridge incident: "You never know what somebody's day looks like...Somebody's not having the same day you're having."

Related Post: Umpire Joe West Officiates 5,000th Regular Season Game (6/20/17).

Concentration on the task at hand—the game—might similarly disarm a potential abuser, akin to the simple action of ignoring a yelling coach or player while the ball is in play. Continuing to call the live-ball action might also give an official time to prepare a metered response (which portrays confidence). If appropriate, decisively addressing the issue during a dead ball period or between innings before it turns abusive may also deescalate the situation. Issuing a warning or other stern language that establishes a clear boundary might also stop the problem before it starts. Nearly all sports' rulebooks support disciplinary action, up to and including ejection, for abuse.

Conclusion: When it comes to officiating and game-based mental health, playing field abuse is an unfortunate reality. However, certain wellness techniques may help recalibrate an official's disposition before, during, or after an encounter with one of the sports world's bad actors. Understanding that even if the insults are personal, the abuse isn't ordinarily about the official relieves the emotional pressure that comes with being on the receiving end of abuse, while employing grounding or refocusing techniques helps combat the emotional consequences of the most unwelcome of on-field interactions.

Related Link: Verbal abuse from parents, coaches is causing a referee shortage (Washington Post)

Related Link: Match officials shouldn't have to put up with the abuse they receive (RTE)

Related Link: Abuse, pay driving referees away in public high schools (USA Today)

Related Link: Refs say a culture of abuse has to change (USA Today)

|

| Let's talk about abuse of officials. |

In this article, we'll attempt to introduce the most common wellness tactics that relate to officiating: namely, dealing with verbal abuse and its associated environment.

In late June, off-duty MLB Umpire John Tumpane helped save a woman's life on the Roberto Clemente Bridge after she seemed poised to jump into the Allegheny River below. Among the woman's chief concerns were, "no one wants to help me," "I'm better off on this side," and "You don't care about me."

Among Tumpane's remarks were, "Let's talk this out," "We want you to get better," and "I'll never forget you."

The following discussion pertains largely to mental health challenges which occur before, during, or after an athletic contest. Sometimes, this "after" can be hours. Sometimes, it might even be days or weeks. If you or someone you know is in crisis or having thoughts of suicide or hopelessness, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. You can also chat online with a trained operator.

|

| MLB Umpire John Tumpane. |

While acknowledging philosopher John Locke's belief that in the state of nature, people are generally peaceful, good, and pleasant, we also dip into Thomas Hobbes' famous line about life: "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

The more games one officiates, the more likely one is to encounter the classical Hobbesian bad actor. A 2012 University of Toronto study found that 92% of hockey referee respondents indicated they had been the recipients of aggression or anger on the ice, while 55% officiated contests that "ran out of control." Nonetheless, 80% of referees and linesmen indicated that they still enjoyed officiating.

|

| Redmond tries saving face by scapegoating. The strategy didn't work: he was still fired. |

Related Post: Gil's Call - The Blame Game (Umpire Scapegoating).

|

| It sure doesn't look like it's about the ump. |

In Plainer Terms: It's about the disturbed state of the participant, not about the official.

Defining Abuse: Verbal or physical abuse of officials can comprise a wide variety of bullying tactics and unwanted aggressive behavior that might include force, a threat, intimidation, or attempt to dominate. It can be a player who hurls personal insults, a coach who threatens to call one's assigner or supervisor, to throwing equipment, kicking dirt, threatening remarks such as "I'll see you in the parking lot," and anything in between.

|

| A firm boundary is vital to stopping abuse. |

Related Link: Ejections - What and Wherefore? Standards for Removal from the Game.

|

| Penalty for abuse might include ejection. |

Related Post: Crew Consultation - Importance of the Call on the Field.

Furthermore, we can all take a page from Tumpane's book and apply it to the ballpark or arena, striving to be better crew-mates through praise, encouragement, and actively striving to strengthen the bonds of kinship and camaraderie both on and off the field. Before, during, and after a game, officials are often other officials' only friends.

|

| Tim Timmons has had enough. |

Prior to conflict, learning the basic principles of self control—the ability to subdue impulses in order to achieve longer-term goals—will help later on when an incident does occur. In an abuse situation, the impulse is the self-critical emotional one, while the longer-term goal is simply to exit the situation in a healthy mental state.

Depersonalization—becoming a detached observer of your self or situation—when employed sparingly and strategically during an abusive episode may provide even further perspective to sterilize the abuse. Just be sure the strategy is a conscious short-term decision and not a routine way of conducting business. Dissociation is one of Vaillant's neurotic defense mechanisms, which, when taken to an extreme, is not healthy. HOWEVER, the humor that may result is a healthier strategy.

|

| Farrell looks ridiculous yelling at a calm ump. |

|

| Even Jeff Kellogg can't believe Fredi's guff. |

Post-Abuse Abuse: After an official has disciplined a participant for abuse, that participant is likely to get even more abusive. For instance, when officials are physically struck by players or coaches, this violent crime is significantly more likely to occur after the guilty participant has already been ejected from the game. First, the offender is embarrassed for having been called on his/her abusive behavior. Second, the offender thinks "what have I got to lose?" after being disciplined, which is further reinforced by the popular broadcasting term, "get your money's worth." Kill the Umpire culture certainly doesn't help.

Related Post: Did Detroit Throw at Umpire Wolcott? A Visual Analysis (9/14/17).

|

| After getting ejected, UCLA softball coach Fernandez bumped plate umpire Peterson. |

The Four Types of Game Participants: There are generally three or four types of players and coaches, relative to officiating, and participants can bounce between neighboring types during a game, or from game-to-game:

|

| Think: Is this coach an ally or adversary? |

Neutrals: Comprising the bulk of participants, these persons don't go out of their way to build much rapport, but neither will they antagonize officials. Neutrals generally don't interact much with referees and umpires, largely because they are either concentrating on their own game or simply don't bother themselves with officiating matters, which they see as outside of their locus of control. They might exhibit traits both congenial and challenging, though not too notable in either direction.

Adversaries: Some players and coaches thrive off building an adversarial relationship with nearly everyone on the playing field, including officials. For some, a "the world is against me" attitude has helped them succeed before, and, through positive reinforcement, they have adopted the mantra as their playing attitude. These participants may push buttons and attempt to find where the boundary line is, albeit without much malice.

Abusers: These are playground bullies on a sports field. Harassment is routine, yelling is generally constant or often simmering, and the worst thing about it is that the abusive behavior is durable, largely because it has worked for the abuser in the past through a lack of consequences or even a reward (or perceived positive result). Though an official must treat all game participants equally within their class of participation (e.g., more tolerance is shown to a head coach than an assistant coach, but equal tolerance should be extended to both teams' head coaches), an abuser will generally burn an official's fuse a lot quicker than the other three participant types—combined. Don't be afraid to discipline that which is abusive.

|

| Scheurwater remains calm as Buck screams. |

|

| Officials' only true friends? Other officials. |

Related Post: WUA-MLB Relations Deteriorate with New Umpire Protest (8/19/17).

Related Post: WUA Secures Commissioner Meeting, Suspends Protest (8/20/17).

|

| Adrian Johnson uses a warning to stop abuse. |

Except when, again, someone doesn't accept no as an answer.

In officiating, it is an unfortunate reality that abuse is a more-than-regular occurrence, and, fair or not, we have to arm ourselves with tools to prevent potential bullies from turning abusive. Sometimes, we put up with unpleasant behavior to prevent larger displays of abuse (similar to slowly releasing a steam valve so as to relieve pressure within a pipe so as to prevent the pipe from bursting), and other times we must warn or use a "stop sign" to reseal the metal.

Tact, composure, and demeanor go a long way in officiating. Confidence in game-calling—or even faux confidence—tells potential abusers that one is sure of the calls being made, and not susceptible to intimidation techniques. Every so often, humor helps disarm a would-be combatant.

|

| Joe West employs humor to display "strength." |

West explained a lesson taught to him by Hall of Famer Doug Harvey: "Don't let them ruin your day. You're having a good day. If they give you trouble to kick them out, kick them out. But don't let it ruin your day," a similar message to Tumpane's words after the bridge incident: "You never know what somebody's day looks like...Somebody's not having the same day you're having."

Related Post: Umpire Joe West Officiates 5,000th Regular Season Game (6/20/17).

Concentration on the task at hand—the game—might similarly disarm a potential abuser, akin to the simple action of ignoring a yelling coach or player while the ball is in play. Continuing to call the live-ball action might also give an official time to prepare a metered response (which portrays confidence). If appropriate, decisively addressing the issue during a dead ball period or between innings before it turns abusive may also deescalate the situation. Issuing a warning or other stern language that establishes a clear boundary might also stop the problem before it starts. Nearly all sports' rulebooks support disciplinary action, up to and including ejection, for abuse.

|

| Is this really about Gooch, or about Joe? |

Related Link: Verbal abuse from parents, coaches is causing a referee shortage (Washington Post)

Related Link: Match officials shouldn't have to put up with the abuse they receive (RTE)

Related Link: Abuse, pay driving referees away in public high schools (USA Today)

Related Link: Refs say a culture of abuse has to change (USA Today)

Labels:

Articles

,

Gil's Call

,

Mental Health

,

UEFL

,

UEFL University

,

Umpire Abuse

,

Umpire Odds/Ends

Monday, October 9, 2017

MLB Ejection P-1 - Mark Wegner (1; John Farrell)

HP Umpire Mark Wegner ejected Red Sox Manager John Farrell (strike three call; QOCY) in the bottom of the 2nd inning of the Astros-Red Sox ALDS game. With one out and the bases loaded, Red Sox batter Dustin Pedroia took a 2-2 curveball from Astros pitcher Charlie Morton for a called third strike. Replays indicate the pitch was located over the inner edge of home plate and above the hollow of the knee (px -.885, pz 1.614 [sz_bot 1.487]), the call was correct.* At the time of the ejection, the Astros were leading, 2-1. The Astros ultimately won the contest, 5-4.

This is Mark Wegner (14)'s first ejection of the 2017 MLB postseason.

Mark Wegner now has 12 points in the UEFL Standings (8 Prev + 2 MLB + 2 Correct Call = 12).

Crew Chief Ted Barrett now has 19 points in Crew Division (18 Previous + 1 Correct Call = 19).

*UEFL Rule 6-2-b-1 (Kulpa Rule): |0| < STRIKE < |.748| < BORDERLINE < |.914| < BALL.

*This pitch was located 0.348 horizontal inches from being deemed an incorrect call.

Related Post: Zobrist - Computer Ump Would Have Called Strike 3, Too (8/15/17).

This is the 185th ejection report of 2017, 1st of the postseason.

This is the 87th Manager ejection of 2017.

This is Boston's 6th ejection of 2017, 4th in the AL East (NYY, TOR 11; TB 7; BOS 6; BAL 4).

This is John Farrell's 3rd ejection of 2017, 1st since July 22 (Phil Cuzzi; QOC = Y [Balls/Strikes]).

This is Mark Wegner's first ejection since July 15, 2016 (Bob Melvin; QOC = Y [Balls/Strikes]).

Wrap: Houston Astros vs. Boston Red Sox, 10/9/17 | Video as follows:

This is Mark Wegner (14)'s first ejection of the 2017 MLB postseason.

Mark Wegner now has 12 points in the UEFL Standings (8 Prev + 2 MLB + 2 Correct Call = 12).

Crew Chief Ted Barrett now has 19 points in Crew Division (18 Previous + 1 Correct Call = 19).

*UEFL Rule 6-2-b-1 (Kulpa Rule): |0| < STRIKE < |.748| < BORDERLINE < |.914| < BALL.

*This pitch was located 0.348 horizontal inches from being deemed an incorrect call.

Related Post: Zobrist - Computer Ump Would Have Called Strike 3, Too (8/15/17).

This is the 185th ejection report of 2017, 1st of the postseason.

This is the 87th Manager ejection of 2017.

This is Boston's 6th ejection of 2017, 4th in the AL East (NYY, TOR 11; TB 7; BOS 6; BAL 4).

This is John Farrell's 3rd ejection of 2017, 1st since July 22 (Phil Cuzzi; QOC = Y [Balls/Strikes]).

This is Mark Wegner's first ejection since July 15, 2016 (Bob Melvin; QOC = Y [Balls/Strikes]).

Wrap: Houston Astros vs. Boston Red Sox, 10/9/17 | Video as follows:

Labels:

Balls/Strikes

,

BOS

,

Ejections

,

John Farrell

,

Kulpa Rule

,

Mark Wegner

,

QOCY

,

UEFL

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)